Vocabulary Survey

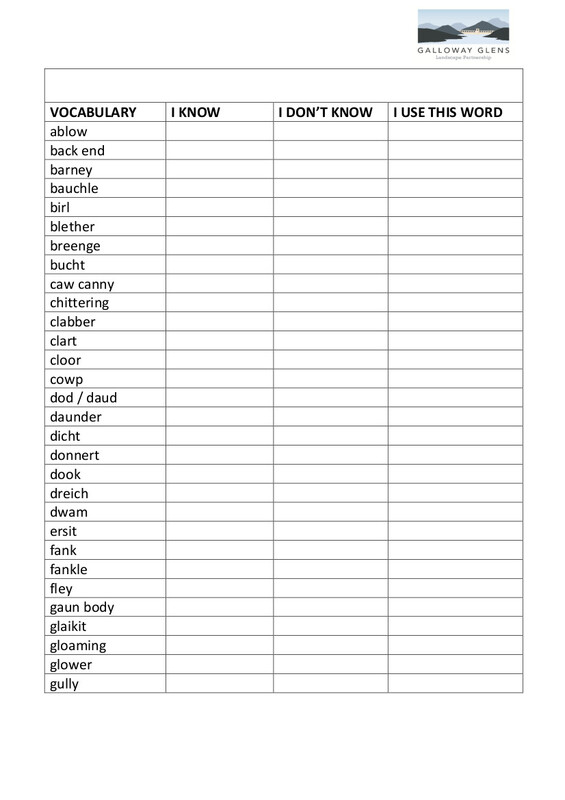

We may suffer from a bit of a cultural cringe where language is concerned, but we are fascinated by it all the same. As part of this project I produced a questionnaire asking if certain words were known or unknown to those who filled it in. Another column asked whether those who knew a certain word actually used it, because all of us have active and passive vocabularies. There are many words we know and understand but, for various reasons, are never called upon to use. One of the people I interviewed knew most of the words on the questionnaire but no longer used many of them. When she no longer lived on a farm or spoke to farm workers, she had no need for many of the farm-based words. Words, she was reminding me, do not exist in a vacuum, but exist and are used within specific contexts. The questionnaire was loosely-based on Riach’s A Galloway Glossary, published in 1988. That was a fairly comprehensive academic study of our local vocabulary. The Glens questionnaire on the other hand was a more personal affair. Most of the words on it are words I use in my daily life though one or two are a bit more abstruse.

The questionnaire was received with a great deal of interest. Originally I had intended to use it as part of a conversation with people I interviewed, but when word of it got out people contacted the Galloway Glens office to pick up copies, to fill them in and return them, often with annotations and explanations added. Those who filled in the questionnaire then were really a self-selecting group of people who thought the topic was an important one. It was obvious from the discussion about the words on the sheet even just in my own family that people were very interested and heavily invested in what they often described as “the auld Scots words” despite the fact that they were in fact confirming that many of the “auld” words were still very much in use. The questionnaire indeed gave many people a great deal of pleasure as well as food for thought as they discussed exactly what a word meant, remembered it being used by family members now no longer living, or just explained it to younger family members who had never heard it. This kind of engagement within families or groups of friends is a vital and valuable thing. During the Covid pandemic in 2020, several people reported discussing it on Zoom or Face Time when unable to visit family members. It may have been about words and language in this instance but such inter-generational engagement even if only for an hour or two can help alleviate loneliness and isolation and bring people together and remind us how language binds us together.

That said, there were one or two things I wish I had made clearer on the sheet. I had deliberately not given context or definitions in case that led people in a certain direction. This meant, though, that a couple of words caused problems. “Back enn” was taken by some people to mean the rear of something, when in fact it really refers in Scots to Autumn, the back end of the year. And “gully” was sometimes understood as in English to refer to a cleft between rocks or a deep valley. It is the word my granny always used for a big knife, a carving knife. Indeed my sister-in-law came out with it in this sense just last week . And she is younger than me, so it is still in use. Two other words were deliberately put in though I suspected they might be relatively rare: “gaun-body” and “through-bin”. A “gaun-body” is a tramp, someone who wanders the countryside, and a “through-bin” is a long stone that goes through a drystane dyke to help tie it together. We rarely see tramps of that kind nowadays, and only people on farms or working with stone are likely to think about through-bins.

Looking at the data from my self-selecting group it is clear that there has been a decline in the use of Scots vocabulary items over the last century. If we look briefly at the charts for those born in the 1920s and those born after 1970, roughly a fifty year period0) the number of words not known goes up considerably. And if they are not known they are not used.

Some words are still very much in use, including:

- Blether: to talk/chat informally

- Clart: to cover something roughly (generally with mud)

- Cowp: to tip over, the Council Recycling Centre

- Dreich: dreary

- Glaikit: singularly stupid

- Oxter: the armpit

Some words which have fallen out of use surprised me because, to me, they are still very present and I hear them all the time as I go about my daily life:

- Stravaig: an aimless wander

- Dwam: away in a dwam, away in a dream or world of one’s own

- Fley: a fright

- Lowp: to jump

- Howk: to dig

Two words that were well known to the older generation but seem to have fallen out of use are “jaup” and “jaw”. Jaup is to spurt, as in the hot fat is “jaupin oot o the fryin pan”. To “jaw” water is to throw it quickly out of a cup or bucket.

Other words that seem to be on the way out are perhaps less surprising:

- Peeweet: lapwing. A bird that is no longer common here.

- Gaun-body: a tramp

- Stankey: a moor-hen

- Trauchle: a weary trudge. Trauchled = exhausted

Interestingly one of the words that people marked increasingly as “don’t know” was “stenter”, a clothes pole. This word, which I have always used and which is still used routinely by many of us who hang out our washing to dry, seems to be a fairly recent addition to the vocabulary of Scots according to the dictionary. It is also noted as being a Kirkcudbrightshire word.

People born in the 1940s and 1950s still seem to be strongly attached to many of the words on the questionnaire before usage seems to decline in the active vocabulary of those born in the 1960s and the 1970s. Obviously there are many reasons for this. This was the time when television ownership became gradually more widespread. Television and radio, especially when broadcast by the BBC, favoured Received Pronunciation over regional accents. Cinema and Hollywood glamour also had a huge influence in convincing us that the way we spoke was somehow less socially acceptable. And now, despite many advances in our attitude to local dialects and to Scots in particular, English has become the dominant language on the internet. Many of us will have spent an entertaining hour or two trying to utilise some computer-based voice-recognition system which just cannot deal with a Scottish accent never mind a Scots-inflected vocabulary. Jings!

The cultural cringe, though, seems to be still going strong. We love to see these words printed on a tea-towel or on a mug but because of outmoded social conventions, feel we cannot say them out loud. We need to remember that language is there for communication. We should be able to use appropriate language in appropriate situations to aid rather than block communication. It was pleasing to receive comments from people who had moved into the Glens area and were fascinated by the language they heard around them. Pleasing because this spoke of an implied inclusivity.

Spoken without embarrassment and delivered honestly any language carries the dignity of its speaker. I hope this is what comes across in the clips I want to share with you from those brave souls who agreed to be interviewed by me. I am indebted to every one of them and would like to thank them for their time, their generosity, and their patience. It was a learning process for them and for myself. As the interviews went on they grew more confident and developed their comments more fully while I learned (I hope) to shut up and stop butting-in. Language is a fluid medium and one thing you will hear very clearly in these clips is the way that every one of us moved seamlessly from Scots to English and back again. Sometimes within one sentence. Sometimes with the same word. In one short exchange, Agnes McQueen referred to her father as “dad”, “faither”, and “fether”. Language is a living thing. It’s about communicating, being connected to others. And those connections are vitally important. None of us nowadays is unconnected, though it is sometimes not easy to gain access to those connections.. Many living in this area have been away for work or education. Some have been abroad in the Services, Many of us have relatives abroad who bring new words to our vocabulary. Again, as Agnes McQueen implied, words do not exist in a vacuum. There is always a human context.

The second aspect of the project was to use the recordings to contribute to a social history of the Galloway Glens. Again, this is not an academic study, but a response to what ordinary people said about their lives. By “ordinary” I do not mean any disrespect but rather to highlight the fact that these particular voices represent a spectrum of experience gained by living in this area. To this end the questions asked ranged from gaining a biographical overview of someone’s life to asking what they remembered about areas such as school, work, holidays, recreation, the changes they have seen. The interviews were set to begin in early 2020 but had to be put on hold for a long time because of the various restrictions and lock-downs associated with the Covid 19 pandemic. When it was safe to visit and record older people the interviews continued.

Now, the oldest person I interviewed was born in 1923, the youngest in 1970, so the history we are looking at is relatively recent, yet it is clear that things were very different back then. Many people had no inside toilets, no running water in their houses, no automatic washing machines, no central heating, no television, no telephone or internet, no mobile phones. It is very likely that they did not have a car, though they did have quite a good bus service and, until the early 1960s, they had the railway. The pace of life was a bit slower than today, but in many ways it was more physically demanding.

Nowadays we have more and we expect more. Children growing up in the Galloway Glens now are encouraged to think beyond their immediate surroundings much more than they were before. Paradoxically this can give them a greater sense of the value of the place where they grew up so that when they are adults they want to give something back to the place that formed them. Until the social upheaval caused by World War Two, many people were denied the opportunity to develop through education and travel.

Yet no-one I interviewed really complained about the conditions in which they grew up. Indeed, many of them pointed out that “it was juist normal. We didnae ken onything else.”